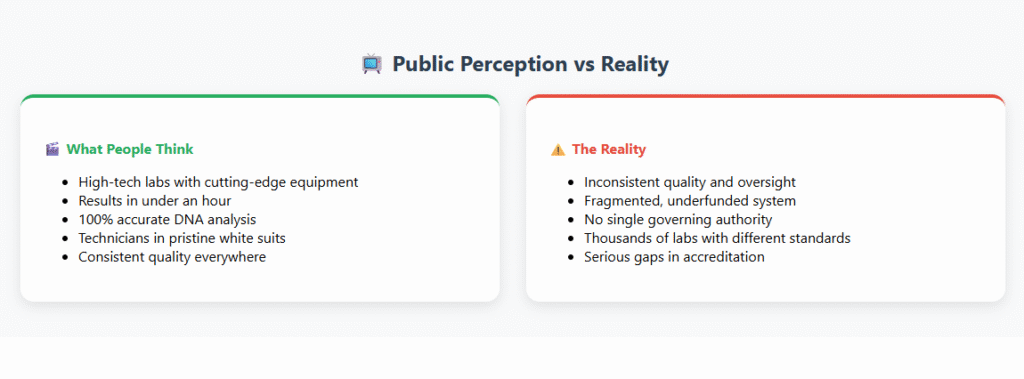

When you hear the word forensics, what comes to mind?

Technicians in white suits behind yellow crime scene tape. Modern glass and metal labs with the newest and best equipment, and answers that arrive in under an hour.

The reality?

Much different and far more concerning.

Behind the scenes, forensic science providers across the United States are facing what Brian Gestring calls an invisible crisis. Something that directly affects the accuracy, reliability, and trustworthiness of forensic work used in criminal investigations.

And Brian Gestring would know.

With more than 30 years in the field, Gestring has seen the issues from every angle. On the sharp edge of the spear, he has been a scene investigator and a bench examiner in the crime lab. He has supervised and managed some of the largest and busiest crime laboratories in the country and managed an entire state’s forensic laboratory accreditation program. He responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center and worked on identifying the victims of the attacks. As an academic, he has taught undergraduate and graduate students, directed a university forensic science program and conducted forensic science research. Throughout his career, Gestring has taught federal, state, and local law enforcement personnel, prosecutors and defense attorneys, and forensic practitioners

Few people are more qualified to talk about the state of forensic science today.

Let’s break down his message, why it matters, and what he thinks can be done about it.

The Disconnect Between TV and Reality

Public trust in forensics is sky high. After all, who doesn’t believe in DNA?

But according to Gestring, that perception hides a dangerous truth. The quality and oversight of forensic services in the United States are inconsistent, fragmented, and underfunded.

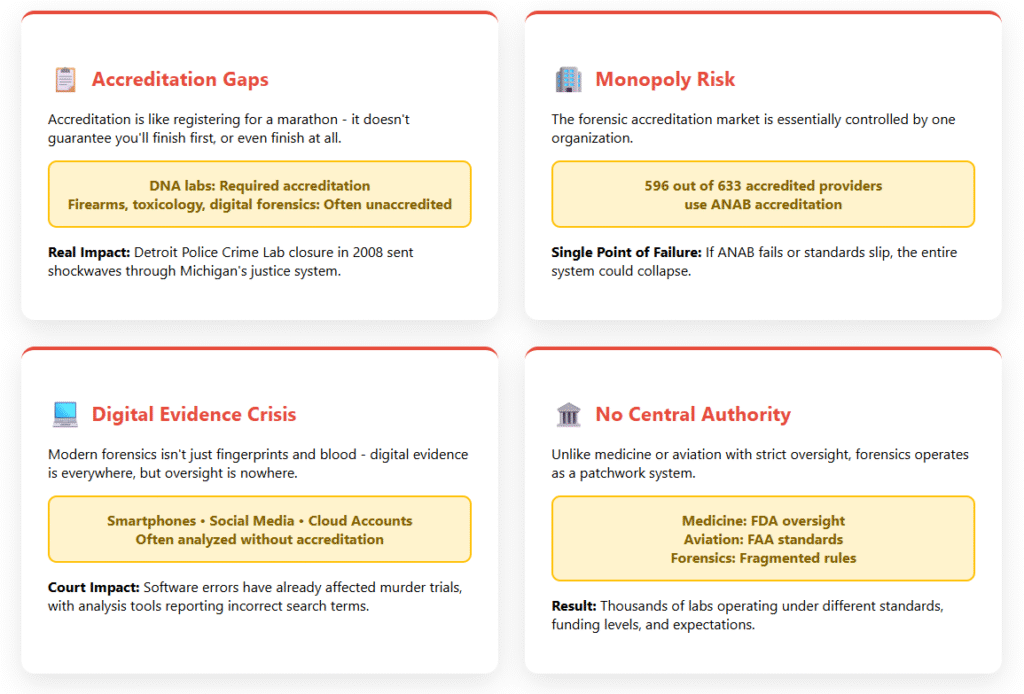

Unlike medicine or aviation where strict standards, central oversight, and redundant safety systems are non-negotiable, forensics has no single governing authority.

Instead, thousands of individual labs, agencies, and providers operate under different rules, levels of funding, and expectations.

The result is a patchwork system with serious cracks.

Why Accreditation Isn’t Enough

Some in the field point to accreditation as the solution. Aren’t accredited providers reliable?

Not exactly.

Gestring points out that accreditation is like running a marathon. You must do a lot to get ready, but registering for the race does not mean you’ll finish first or even finish at all. Accreditation is the first step toward quality, but it is only the first step, and it is possible for an accredited provider not to be reliable.

Even worse, accreditation is inconsistent. There are no universal requirements to be accredited.

DNA labs must be accredited to access national databanks, but many other disciplines like firearms, toxicology, or digital forensics often operate without it.

That is how we ended up with disasters like the Detroit Police Crime Lab closure in 2008, which sent shockwaves throughout Michigan.

One Vendor to Rule Them All

Here is another red flag. The forensic accreditation market is basically a monopoly.

Of the 633 accredited providers in the United States, 596 are accredited by ANAB, the ANSI National Accreditation Board.

That creates what Gestring considers a single point failure risk. If ANAB were to stop accrediting forensic labs, or if its standards slipped, the entire system could collapse.

It is like having only one airline in the country. One critical failure, and everyone suffers.

The Digital Evidence Problem

Forensic science is not just about fingerprints and blood spatter anymore. Today, digital evidence is everywhere, from smartphones to social media to cloud accounts.

But here is the scary part. Digital forensics providers often ignore accreditation entirely.

That gap has already shown up in court. In one murder trial, software used for analysis mistakenly reported “chloroform” searches when the actual queries were for “Myspace.” Imagine the consequences of that kind of error.

As digital evidence becomes the centerpiece of more cases, the risk only grows.

We Don’t Even Know How Big the System Is

You would think the United States has a complete list of forensic providers. It does not.

No one actually knows how many forensic service agencies exist. Estimates suggest there are far more labs and providers than reported.

For example, New York has 22 accredited labs, but Gestring estimates there could be ten times that number of agencies performing forensic work statewide.

Without accurate data, it is impossible to know the true scope of the crisis or to ensure consistency across providers.

Voluntary Compliance and Resistance

Here is the core of the invisible crisis. Most forensic standards are voluntary.

Yes, national commissions and expert panels have issued recommendations like the 2009 National Academy of Sciences report that called for sweeping reform.

But implementation has been spotty at best.

Many agencies resist change, often due to budget limits or cultural inertia. And without a central authority to enforce higher standards, reforms stall.

The Money Problem

Forensic labs are chronically underfunded.

It is a story as old as the field itself. Back in 1910, Dr. Edmond Locard founded one of the world’s first forensic labs in Lyon, France. He operated it out of two attic rooms and had to rely on borrowed resources.

A century later, many United States forensic providers are still operating on shoestring budgets, struggling to keep up with backlogs, training, and technology.

It is hard to deliver reliability when you do not even have enough staff or equipment.

What Brian Gestring Proposes

Despite all these challenges, Gestring is not a pessimist. He is pragmatic. He believes the forensic community can fix itself if it chooses to.

Here are his key proposals.

1. Use NAFSB’s Influence

The recently developed National Association of Forensic Science Boards represents 44 percent of ANAB accredited providers. That is a huge block.

If NAFSB encourages its members to raise their standards, the ripple effect could push the entire system to improve, just like how California’s strict car emission rules influence the whole auto industry.

2. Restore Rigorous Standards

Many standards were watered down when forensic accreditation programs moved from small companies only providing accreditation for forensic providers to large companies that accredit many different industries. Over time, reviews and checks within forensic labs have been watered down. Gestring calls for reinstating strong administrative and technical reviews, along with requiring each provider to have a technical leader. Someone who is responsible for keeping up with all the changes in their field and making the technical decisions.

3. Build Redundancy in Accreditation

Right now, ANAB, a privately owned company, dominates the forensic accreditation market. Gestring suggests encouraging other accreditation vendors to enter the market.

He also points to the National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program, an accreditation vendor run out of the National Institute of Science & Technology. NIST is an agency of the federal government and NVLAP could easily add a forensic accreditation program. This would add some redundancy, but also stability because the government has an obligation to provide these services while a private company will only do it for as long as it is profitable.

4. Federal Support Without Heavy Regulation

Gestring is not looking for federal regulation of forensic labs. The recent reevaluation of a long-standing legal precedent by the US supreme court essentially closed this door. But Gestring believes that the federal government should have a role in supporting forensic providers. Through supporting the expansion of NVLAP, targeted grant funding opportunities, and better data collection by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the federal government can work with state and local authorities to increase both the quality of the work forensic providers do and the resilience of the system that they work within.

Why This Matters

Forensic evidence is supposed to round the sharp edges of the criminal justice system. It can tell a story when there are no witnesses that had seen what had happened. It doesn’t get emotional, and it can’t lie.

The first time DNA evidence was used in a criminal case; it exonerated someone before it drew authorities attention to the true perpetrator.

When it is weak, inconsistent or unreliable, it undermines trust, produces errors, and ruins lives.

Gestring’s career has been about building reliability into the system, from reducing lab backlogs to pioneering standards for DNA testing and lab reports.

And now, he is sounding the alarm.

The invisible crisis may not grab headlines like a high-profile trial, but it is just as important. The very foundation of justice depends on it.

Key Takeaway

Brian Gestring’s message is simple but urgent. Forensic science must take responsibility for its own quality.

The field has reformed itself before. In the 1970s, Duayne Dillon’s critique of the FBI lab sparked the creation of ASCLD and ASCLD LAB, which reshaped standards for decades.

The same spirit of self-correction is needed now.

If forensic providers do not address the invisible crisis, the cracks in the system will only widen and public trust may not survive the fallout.

Final Thought

Brian Gestring has spent his career at the crossroads of science, justice, and policy. He has been on the ground at crime scenes, in the lab overseeing DNA programs, in the classroom shaping new scientists, and in boardrooms pushing for reform.

His conclusion is clear.

The responsibility lies with the forensic community itself. Accreditation must mean more. Oversight must be real. Standards must rise.

And while the public may never see this invisible crisis, they will feel its consequences unless the field takes action now.